The Noise – A Surge of High-Profile Incidents

If you’ve felt like 2025 has brought a constant stream of disturbing aviation news, you’re not imagining things — at least not in terms of media coverage. The past 18 months have seen a cluster of high-profile incidents that, while rare in occurrence, have captured intense public attention and driven a perception that the skies are growing less safe.

Here are the major incidents that have shaped public sentiment:

• January 2024 – Alaska Airlines Flight 1282: A Boeing 737 MAX 9 suffered a mid‑flight door plug detachment shortly after takeoff from Portland. The cabin partially depressurized. Though no passengers were seriously injured, passenger videos went viral, prompting a global grounding of MAX 9 aircraft by the FAA and other regulators.

• June 2024 – Boeing Dreamliner Whistleblower: A former Boeing quality engineer raised safety concerns regarding structural flaws and improperly shimmed fuselage joints on the 787 Dreamliner. His testimony to the FAA and U.S. Senate reignited public and regulatory scrutiny of Boeing’s manufacturing quality controls.

• December 2024 – Jeju Air Flight 2216 Crash: A Jeju Air Boeing 737‑800 crashed while attempting a second landing at Muan International Airport in South Korea after a suspected bird strike. The aircraft belly‑landed with gear retracted, overran the runway, and struck a concrete embankment. It disintegrated on impact, killing 179 of 181 occupants. Investigators confirmed bird DNA in the engines and cited a combination of mechanical failure, bird ingestion, and inadequate runway infrastructure as contributing factors.

• January 2025 – Potomac River Mid‑Air Collision: A Bombardier CRJ‑700 (American Eagle Flight 5342) and a U.S. Army UH‑60L Black Hawk helicopter collided at low altitude over the Potomac River near Reagan National Airport in Washington, D.C. All 67 people aboard both aircraft were killed. Preliminary NTSB findings cite possible communication failures, insufficient vertical separation, and air traffic control staffing issues. It was the first fatal U.S. commercial airline accident since 2009.

• April 2025 – Hudson River Helicopter Crash: On April 10, a Bell 206L-4 sightseeing helicopter operated by New York Helicopter broke apart mid‑air near Manhattan and crashed into the Hudson River. All six people on board (five tourists and the pilot) were killed. The NTSB cited suspected rotor system failure, and the FAA grounded the operator pending a full airworthiness review.

• June 2025 – Air India Flight 171 Crash: A Boeing 787‑8 Dreamliner en route from Ahmedabad to London Gatwick crashed into a hostel shortly after takeoff on June 12. Of the 242 people on board, only one passenger survived. At least 39 people on the ground were also killed, bringing the death toll to approximately 280. The crew had issued a Mayday call reporting loss of power or thrust. This was the first fatal hull-loss involving a 787 Dreamliner, and investigations are ongoing under Indian, UK, and U.S. oversight.

Each of these events generated widespread media coverage, intense speculation, and in some cases, swift regulatory action. But perhaps the more important pattern isn’t what happened on board these flights — it’s how quickly and vividly these stories reached millions of people. In an age when passengers livestream emergencies and headlines are designed to go viral, the psychological impact is immediate and amplified—often without regard to historical context or the rarity of such events.

The result? A growing gap between how safe flying actually is — and how safe it feels.

What the Data Actually Shows

While recent headlines have painted a picture of an industry in turmoil, the numbers tell a different story—one that suggests that commercial aviation remains remarkably safe, and in some respects, is improving.

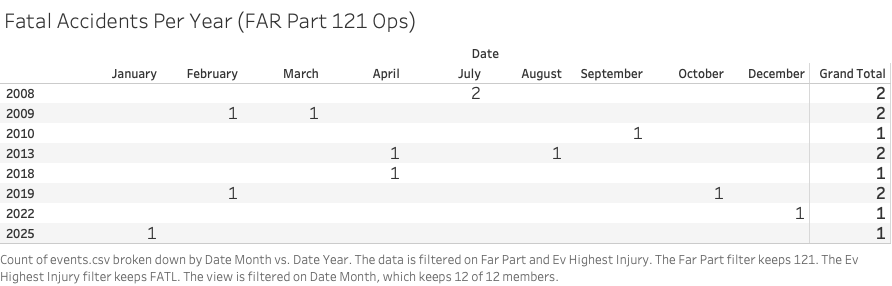

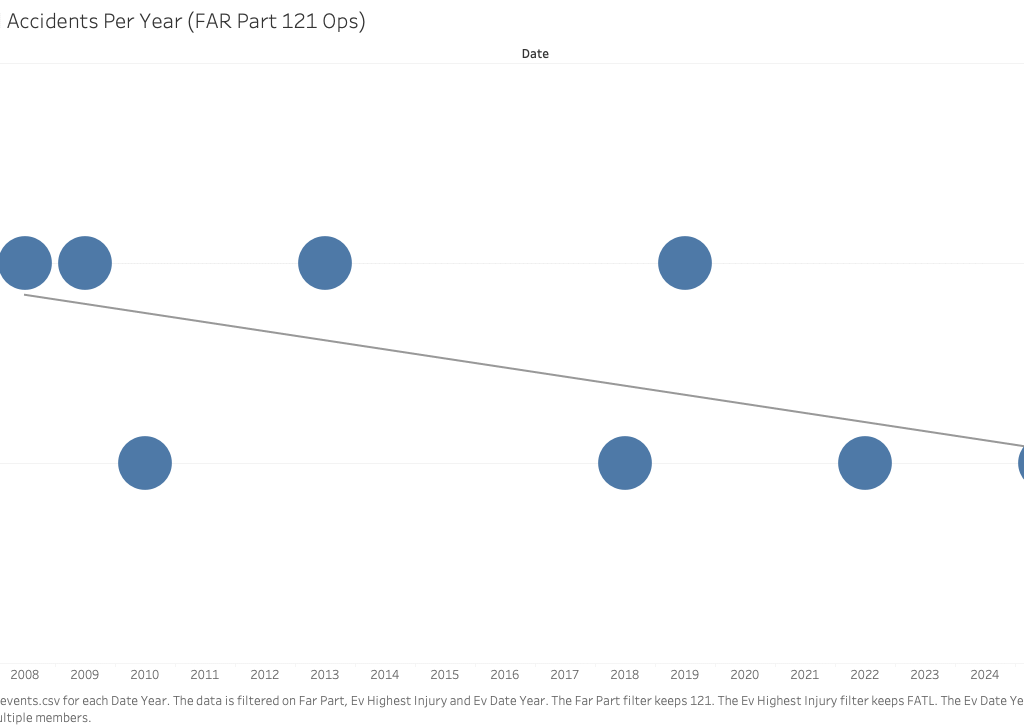

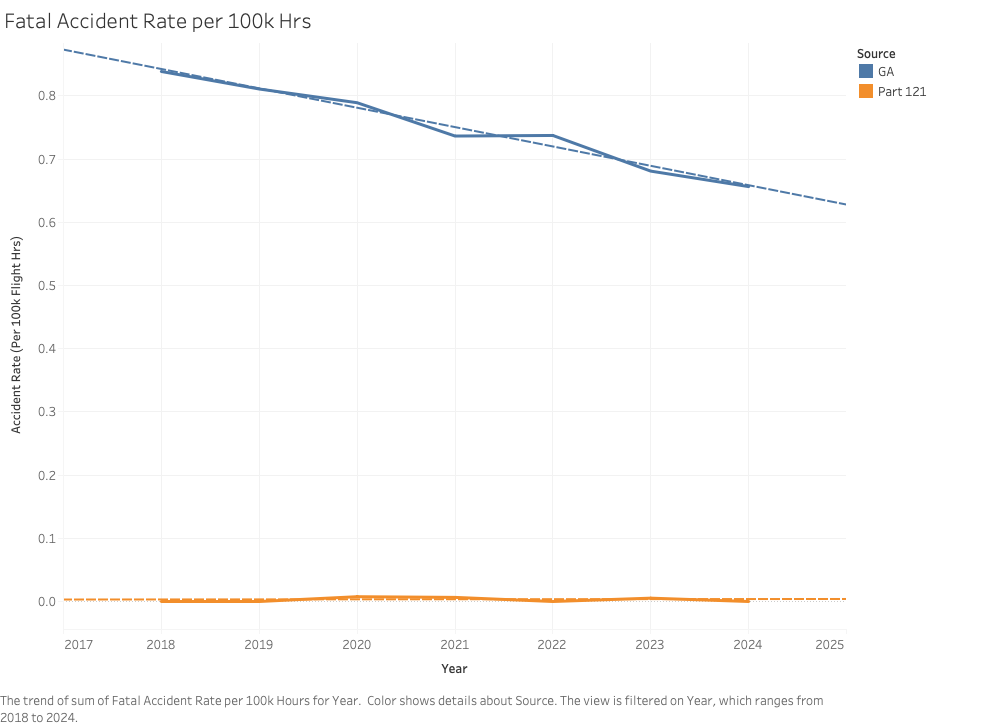

Let’s begin with the reality of airline travel in the United States. Flights operating under US Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) Part 121—this includes nearly all scheduled passenger airline operations—have maintained an extraordinary safety record. In fact, from 2009 through the end of 2024, there were no fatal crashes involving Part 121 passenger flights in the U.S. That’s more than 15 years without a single fatal crash in a category that includes thousands of daily departures. Even with the tragic collision over the Potomac River in January 2025, this long trend underscores how rare fatal airline crashes have become.

This remarkable safety performance isn’t due to chance. It’s the result of decades of refinement in airline operations, flight training, aircraft design, and regulatory oversight. Modern aircraft undergo intense scrutiny, and today’s airspace is carefully monitored by redundant safety systems and highly trained crews. Although isolated incidents will always occur, the broader picture shows that U.S. airline travel is as safe as it has ever been.

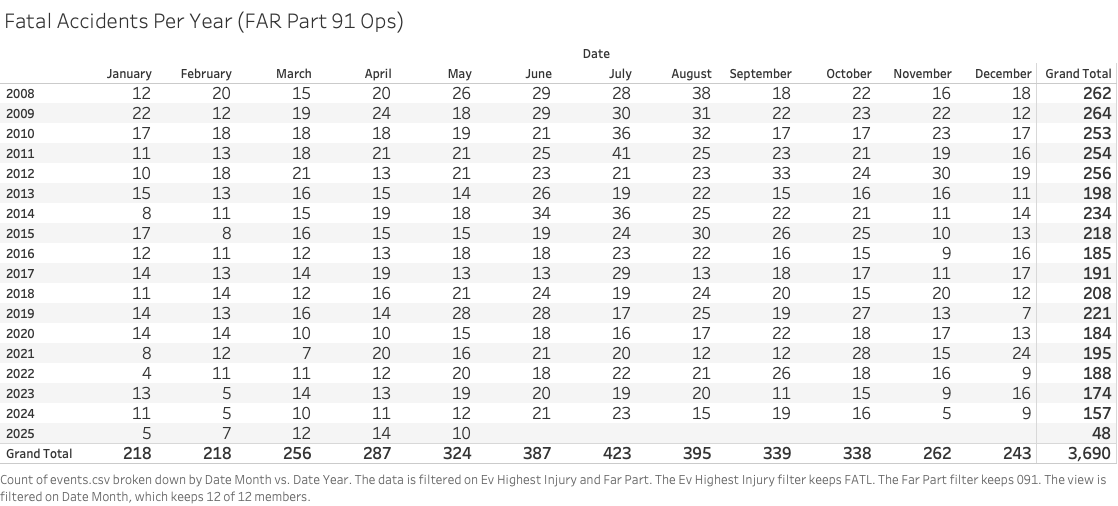

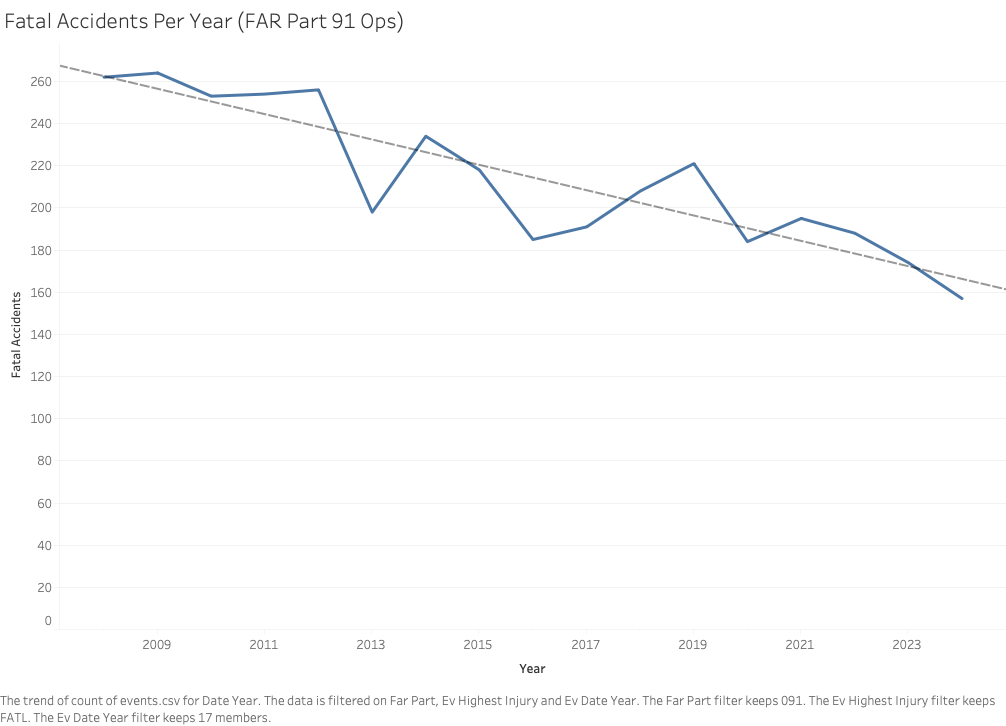

Turning to general aviation, the story is more nuanced, but still encouraging. General aviation—flights conducted under FAR Part 91—encompasses a wide range of operations including private pilots, instructional flights, air tours, and more. Unlike Part 121 operations, general aviation sees a higher number of accidents overall, due to factors like weather, pilot experience, and the diversity of aircraft involved. But even here, progress is clear. The annual Joseph T. Nall Report, which analyzes accident trends in general aviation, has shown a steady decline in both total and fatal accident rates over the past decade.

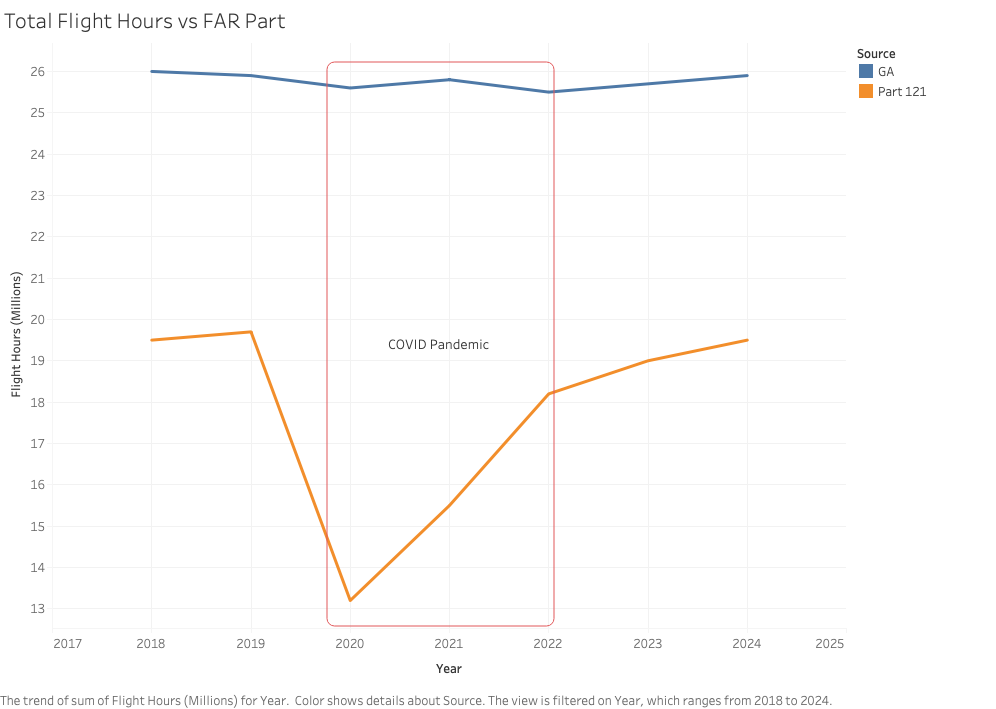

Of course, some may ask: Are accident rates falling simply because people are flying less? After all, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused a historic drop in air travel. But more recent data suggests that both airline and general aviation activity have recovered. Flight hours in the Part 121 category have now returned to—or even surpassed—pre-pandemic levels. And general aviation, particularly in training and recreational sectors, is showing a strong rebound as well. This is an important point: if flying activity is back up, yet accident rates are flat or falling, it strengthens the case that safety systems are working.

In short, while the public may feel like aviation is becoming more dangerous, the underlying data from federal sources and independent safety reports tells a far more reassuring story. Even in a year that includes multiple headline-making incidents, the actual rates of accidents—particularly fatal ones—remain low, and in some categories, continue to trend downward.

Why It Feels Like More

If aviation is statistically safer than ever, why does it feel so dangerous?

The answer lies not in the number of accidents, but in how information about those accidents reaches us — and how our brains process that information. In 2025, the experience of hearing about a plane crash is no longer limited to a line in the evening news. It often begins with a video filmed midflight, shared in real time, followed by a flood of updates, expert speculation, and often contradictory reports. News travels faster, spreads wider, and sticks longer.

Today’s news cycle thrives on immediacy and intensity. Every incident, no matter how routine or ultimately harmless, is packaged for virality. Terms like “emergency landing” or “in-flight failure” dominate headlines even when procedures worked exactly as intended and no one was hurt. When paired with dramatic footage from inside the cabin or quotes pulled from shaken passengers, the perception of chaos often overshadows the reality of control.

Social media intensifies this effect. Passengers live-streaming cabin alarms or oxygen mask deployments create a visceral emotional connection — even when the situation is ultimately resolved without injury. And because social platforms reward attention, content featuring aviation emergencies spreads far more aggressively than a line graph showing declining accident rates. The result is a feedback loop: heightened coverage generates more fear, which generates more clicks, which encourages more coverage.

Cognitive psychology also plays a role. We tend to overestimate the likelihood of rare but dramatic events, especially when we can vividly recall recent examples. A well-publicized crash in January and another in June may feel like a pattern, even if each occurred independently and under vastly different circumstances. This is known as the availability heuristic — we judge probability based on how easily we can bring something to mind, not how often it statistically occurs.

There’s also the reality that flying places people in a position of perceived helplessness. When a train derails or a car crashes, we instinctively believe we might have done something differently. When a plane has an emergency, passengers can only wait. That lack of control makes every headline feel personal.

Combine all of these factors — modern media, social amplification, cognitive shortcuts, and emotional framing — and it becomes clear why aviation feels riskier now, even as it’s never been more statistically safe.

So, Is It Safe to Fly?

After examining the headlines, the hard data, and the psychology that shapes our perceptions, the answer to the central question becomes clearer: yes, it is still safe to fly — remarkably so.

The fear many people feel today isn’t irrational; it’s understandable. A wave of dramatic incidents, amplified by 24/7 media and social media platforms, makes it harder than ever to distinguish rare events from common risk. Even seasoned travelers can feel unsettled when they see footage of emergency landings or read about a whistleblower warning of structural issues in the planes they fly.

But those feelings exist within a broader statistical reality. Commercial aviation in the United States — and in much of the world — continues to operate with an exceptionally low accident rate. The long streak of zero fatal Part 121 crashes in the U.S. from 2009 through 2024 was not a statistical fluke. It was a reflection of layered safety systems, technological advancements, and a deeply ingrained safety culture across the aviation industry. Even with the heartbreaking losses of 2025, the data shows that airline operations remain overwhelmingly safe.

General aviation, while different in nature and more vulnerable to risk, is also showing positive trends. With continued emphasis on training, maintenance, and technology, even recreational flying is becoming safer year by year.

That said, aviation safety is not static. Each accident, however rare, reveals areas for improvement — whether it’s pilot training, air traffic control procedures, or aircraft manufacturing standards. The recent scrutiny of Boeing is an example of how the system reacts to emerging concerns. These investigations, audits, and reforms — while unsettling — are also signs that safety oversight is functioning as intended.

In the end, flying has always involved some level of risk. But that risk today is lower than at any other point in the history of air travel. It is a testament to the industry’s resilience that we can analyze one or two tragic events in a year and be shocked — not because flying has become more dangerous, but because the norm has become so safe that even rare deviations stand out.

So yes — despite the headlines, despite the noise — it is still safe to fly.

Final Thoughts

If flying feels more dangerous lately, you’re not alone — but you’re also not seeing the full picture. What makes the news isn’t the norm; it’s the rare event that breaks through decades of steady, hard-won safety. The numbers haven’t changed much. What has changed is how those numbers are framed, filmed, and shared. The skies remain safe, even if the headlines don’t.